Middle East: Trend for ‘golden visa’ schemes accelerating

Source: dw.com

Published: 4 April 2023

European countries are shutting down their visa- or residency-for-investment schemes, worried about corruption and security. Meanwhile, the Middle East is just getting started in the so-called “citizenship industry.”

After the extremist group known as the “Islamic State” took over parts of her own country in 2014, Iraqi journalist Hiba Ahmad started looking for an escape route.

“I just thought I needed a place outside Iraq, to be safe,” she told DW. “So if there is a difficult situation in Iraq, I can leave.”

After investigating online, the Baghdad native decided to buy a small apartment in Turkey and found one she liked for around $40,000 (€36,840), near a small seaside resort about an hour from Istanbul. The “Islamic State” group was defeated in 2017, but she still comes here regularly.

“The reason I come now is because it’s very hot in summer in Baghdad,” Ahmad explained. “It’s calm and peaceful and I stay for two or three months.”

Although Turkey recently tightened residency rules, Ahmad is able to do this because she bought the Turkish apartment. This allows her to regularly renew a two-year visa. Without the real estate investment, she would only get a tourist visa for a month, she explained. Eventually, if she wanted to, Ahmad could even apply for Turkish citizenship.

Golden immigration opportunities

Ahmad’s Turkish visa is just one of the milder and more affordable examples of what are known as residency by investment (RBI) schemes, often colloquially known as “golden visa” programs. There are also citizenship by investment or “golden passport” schemes but these usually require a lot more money, paperwork and time.

In the Middle East, the motivations for both versions of these schemes are the same. Countries offering golden visas or golden passports want to encourage investment and top up foreign currency deposits. For the individuals who participate in them, these schemes can provide them with better lifestyle options, a second passport that offers more travel possibilities and the chance to escape political problems, economic turmoil or conflict back home.

Canada, the US, Ireland and other EU states have all had these schemes too. But it’s only been in the past five years or so that the idea has gained popularity in the Middle East.

Early in March, Egypt made it even easier for foreigners to become Egyptian via investment. The country has had a citizenship by investment, or CBI, plan in place since 2020 but, because of its economic struggles and the need for more international investment and foreign currency, the country relaxed the terms this year.

The United Arab Emirates has had a golden visa scheme since 2019 but overhauled it in 2022, making it cheaper and easier to access.

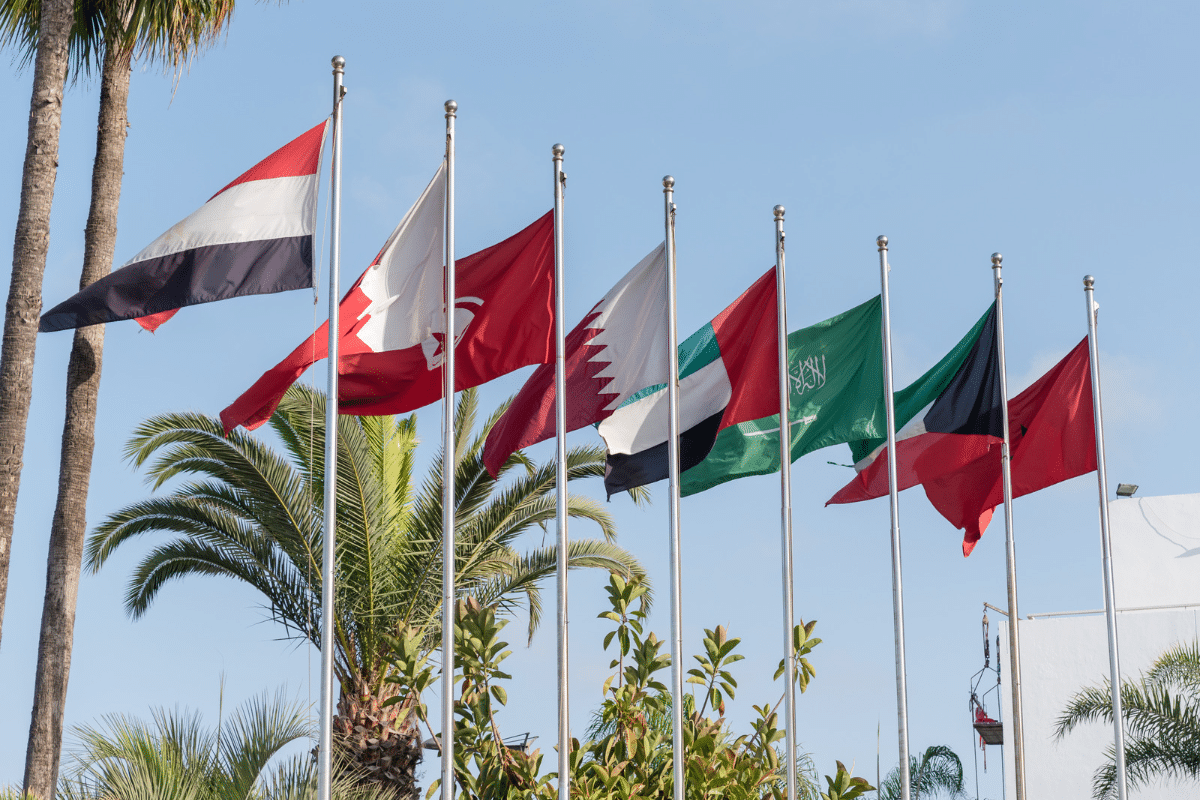

Since 2018, Jordan has had a CBI scheme and in 2020, Qatar began offering a longer, temporary residency in exchange for real estate ownership. Bahrain has had a “golden visa residency” program since 2022 and introduced a “golden license” for large-scale investments this month. And Saudi Arabia launched a “premium residency” scheme this year.

Europe phasing ‘golden visas’ out

“The trend in the Middle East is the reverse of what we are seeing in Europe,” said Jelena Dzankic, a professor at the European University Institute in Italy and co-director of the Global Citizenship Observatory. Dzankic is referring to the fact that in Europe, the golden passport and residency schemes offered by the likes of Portugal, Greece and Cyprus are now being phased out.

In Europe there’s been “progressive abolition of citizenship and residence by investment, due to scandals linked to the scheme and the risks associated with them,” Dzankic explained.

Critics often describe such schemes as nations selling citizenship to the highest bidder, arguing they open the country up to potential security issues, inflated real estate prices and the risk of corruption and money laundering. After the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the EU urged all member states to scrap such schemes for fear they would help sanctions dodgers.

“So I would assume that as one market — the European one — has become inaccessible, people have started to look into viable alternatives,” Dzankic said.

Fast track to citizenship

The modern idea of citizenship by investment dates back to the 1980s.

According to the Switzerland-based Investment Migration Council, or IMC, an umbrella organization for companies involved in the sector, the first CBI program was established in Tonga in 1982, the next by St. Kitts and Nevis in 1984. Small island states, struggling in the aftermath of colonialism, were able to raise funds by offering citizenship or residency in exchange for investment.

Today, most countries offer some sort of route for investors to eventually gain citizenship. But it’s important to differentiate between this and the frequently debated RBI or CBI schemes currently offered in one form or another by around 80 countries, according to the IMC.

In return for substantial investment, these offer either citizenship or residency almost immediately, or via a fast track. Required investments range from about $100,000 in the Caribbean to up to $3.25 million (€2.96 million) in Europe. Some of the schemes require investors to be in the country for a certain amount of days or to set up businesses, while others don’t even need them to visit.

As Dzankic, who has been studying this sector for over a decade, told DW, “a citizenship industry” has grown up around this and often companies involved will also lobby national authorities to introduce more benefits.

Sector observers have said it’s not just Middle Eastern governments that are paying more attention to RBI and CBI schemes. Locals in those countries, especially wealthier individuals in countries experiencing conflict or economic turmoil, such as Lebanon, Iraq, Libya and Syria, are also taking advantage of such schemes abroad.

Who applies for ‘golden visas’?

It is hard to find exact numbers on who is applying for golden passports or visas, or how many there are. State schemes tend to be opaque or slow to publish statistics.

“While there is no definitive data on the exact nationalities of Middle Eastern investors participating in these programs, there are a few patterns,” David Regueiro, a regional representative for the Investment Migration Council, told DW.

For one thing, Middle Eastern investors “are some of the most active consumers of these programs in the world,” he said, with some countries getting over three-quarters of all their applicants for CBI schemes from the region.

“In terms of specific nationalities, investors from countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Lebanon, Syria and Iran are among the most active,” Regueiro added.

Most of the immigrant investors are wealthy with a net worth of somewhere between $2 million to $10 million. But around a quarter of them have less than that, the immigration consultant noted. “So while it’s true that wealthy individuals have been among the most active investors, middle-income earners are also showing more interest,” said Regueiro.

It’s also possible that the less expensive and more accessible such schemes get — such as Egypt’s CBI program or Turkey’s real estate-for-residency plan — and the more difficult circumstances become at home because of things like an economic downturn or climate change, the more that non-millionaires will also consider this kind of move.

“You have a lot of people who can’t afford traditional CBI programs,” said Jeremy Savory, head of the Dubai-based immigration consultancy Savory & Partners. “Maybe there’s a gap in the market for some that start at $50,000, with relevant benefits,” he speculated.

Uncertain future

Whether the programs in the Middle East are more successful than those that came before them remains to be seen, the experts said.

Regueiro believes more new programs will continue to emerge in the Middle East. But, he suggested, “another trend we may see is an increase in the level of scrutiny applied to these programs.”

“The very simple answer is compliance and trust in the process,” Savory argued, arguing that some schemes, such as those in the Caribbean, had been running for decades because they were considered more trustworthy.

“The Middle East is still a young market in this context so what happens with these programs depends on a number of issues,” said Dzankic. That includes how demand develops and how what she calls the “citizenship industry” reacts. While EU countries have been regulated by member states, no such supervision exists in the Middle East.

“So pressures related to democracy and good governance might be less,” she said. “Over time, other concerns may arise out of these programs.”

For example, late last year the EU stopped allowing citizens of Vanuatu visa-free entry into Europe because of concerns about the Pacific country’s loosely regulated CBI scheme. “Then it depends on how states deal with them,” said Dzankic.